Drone scouts are poised to make precision agriculture even more exact as drone technology advances.

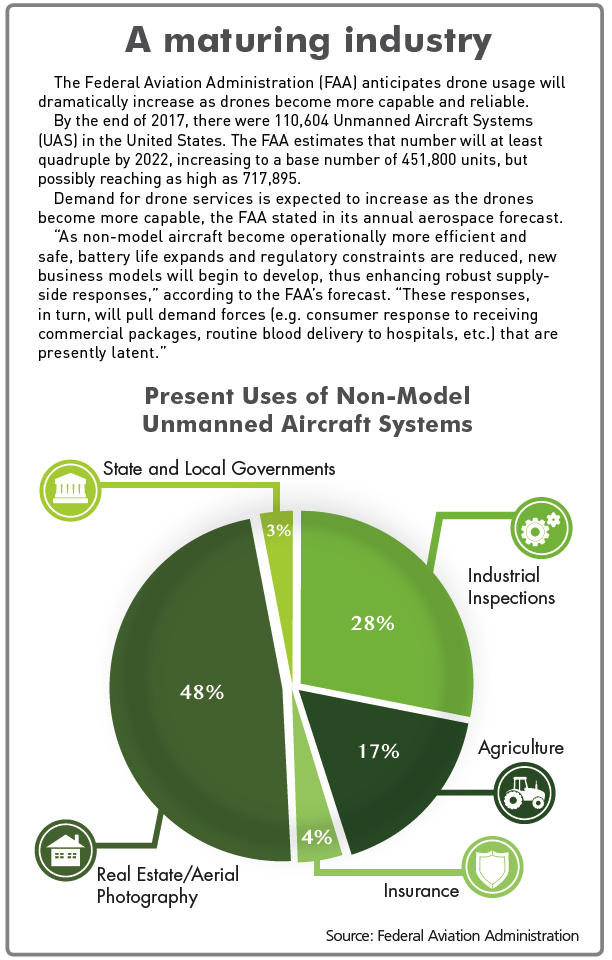

Drones have already arrived at farms, according to the Federal Aviation Administration. Seventeen percent of all commercial registered drones in 2017 were used for agriculture, making it the third-highest use for the machines behind real estate/aerial photography, at 48 percent, and industrial inspection, at 28 percent.

Specialty agriculture is a part of that precision agriculture market for drones. Aeronautics firms such as the French-based company Delair-Tech and the American defense drone contractor AeroVironment are marketing their integrated sensor agriculture drones to specialty crop producers, and the Northwest is a target market.

Seattle-based MicaSense, which sells a multi-spectral drone sensor called RedEdge-M, has been attending growers’ meetings such as the fruit tree growers gathering that took place in Kennewick, Washington. At that meeting, MicaSense CEO Gabriel Torres discussed cropload management analytics that the company is working on.

“We continuously work with farmers and industry leaders in exploring how imagery can influence a certain management practice or help resolve some of the subjectivity around a decision making,” said MicaSense Director of Enterprise Solutions Manal Elarab. “We are committed to continuously exploring new ways to apply imagery analytics in day-to-day farm decisions.”

Academics, too, are studying drone uses for specialty crops. Vegetable Growers News in February 2018 wrote about a partnership between the Rochester Institute of Technology and Cornell University to develop a drone program for identifying snap bean susceptibility to white mold. At Penn State University, two researchers – an engineer and a horticulturalist – are working on a drone program to determine individual blossom coverage and crop load in tree fruit.

Photo: AeroVironment

From soldiers to soybeans

Evolving drone technologies cross from one sector to another. AeroVironment’s ag drone Quantix’s earliest predecessor was a military drone named Pointer that the U.S. Army and Marine Corps used 30 years ago. The company became a major supplier of the U.S. Department of Defense after 9/11 and during the Gulf War and has five programs of record to date with the DOD.

Although Quantix is meant for surveying plants rather than hostiles, its vertical take-off and landing concept came from a military program. The fixed-wing drone launches from a vertical position, like the space shuttle, but levels out like an airplane for long sweeps of crop imagery.

“It’s really the best of both worlds,” said AeroVironment Director of Commercial Sales Mark Dufau.

Technology continues to evolve and companies are finding new features that work best for precision agriculture. One of the basic remote sensing technologies, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), came from satellites programs in the 1960s and 1970s, said MicaSense Remote Sensing Applications Specialist John Sulik.

“There’s a lot you can do,” Sulik said. “It’s just a lot of the older remote sensing techniques aren’t relevant to these higher-value crops. They don’t tell you as much of a story as you need to know.”

MicaSense’s RedEdge-M features five cameras that measure red, green, blue, near-infrared and red edge.

“Multispectral imagery has shown to be a very insightful tool when it comes to scouting your field for stress,” Elarab said. “Indices built from the multispectral imagery aid in understanding the variability within your field and thus guide you to the locations of stress so you collect representative samples that can narrow down the stress cause.”

A few different multi-spectral drone sensors are on the market for growers. Minneapolis-based Sentera on March 28 announced it was selling its AGX710 gimbaled sensor for plug-and-play use with DJI-brand Matrice 200 Series industrial drones. Sentera CEO Eric Taipale said the match makes it “incredibly simple for our customers to gather actionable data from the field.”

“Our customers produce dozens of different index products, and use automated analysis tools across so many different applications in agriculture, forestry and environmental protection,” he said. Sentera’s sensor is packaged with a year of access to a software analytics platform called FieldAgent that delivers crop-scouting insights to help detect disease, pest, and other pressures, identify deficiencies, and assess nutrition status.”

Drones are also traveling longer distances. In France, Delair’s DT18 ag drone is approved for flying beyond visual line of sight, or BVLOS operation (the U.S. FFA requires a waiver for BVLOS flying). The DT18 can be controlled by a 3G wireless phone network and thus can be flown for miles without a control tower.

“In one flight you can cover more than 2,500 acres when regulations allow you to fly high,” said Agriculture and Forestry Product Manager Lenaic Grignard. “We sync our system so that productivity of the crop assessment is very high.”

Wide enough to watch

Drones are expensive and are mostly useful for scouting hard-to-reach areas. So how large does a farm have to be in order to justify the expense?

Independently, both Delair’s Grignard and AeroVironment’s Dufau came up with the same ballpark figure: 1,000 acres.

“In the U.S., when you start to have more than 1,000 acres, it starts to be interesting,” Grignard said. Dufau said that at the thousand-acre threshold, “growers through the Midwest really start to see utility in the system.”

But both were quick to add that in many ways specialty crops are much different than row crops and show a higher return on investment.

“It really comes down to revenue per acre,” Dufau said. “When you get involved in comparisons between Midwestern row crops and specialty crops, those numbers change substantially because of the amount of effort and revenue that’s at stake with a specialty crop vs. corn and beans. That number is substantially smaller as you get into the specialty crops.”

One example, he said, is winegrape growers who are known to deploy drones for a last, quick check of a vineyard as small as five acres.

“It’s not necessarily, ‘What do you find?’” Dufau said. “It’s what you don’t find that gives you that level of assurance that you’re doing what you can to manage it. … (Not) only can they spot problems out there but they also can sleep better at night knowing that there aren’t any problems.”

The higher crop value is one reason drone companies think specialty crop growers are more likely to buy into the technology.

“The adoption rate is slow in row crops, and one of the reasons for this is when you look at the price of the corn, you don’t have the investment capacity to go to this kind of a technology,” Grignard said.

Elarab, of MicaSense, said that specialty growers seem quicker to adapt to the technology.

“High-value crops have been early adaptors of the technology, like vineyards and fruit trees and such,” she said. “There’s also a lot of interest in other crops like coffee and vegetables.

“A lot of people are interested in precision ag and there are various rates of adoption within certain crops. The market is increasing every year. There’s a lot of people getting more excited about incorporating imagery into their management decisions, so definitely there’s a lot of growth going on.”

From data to decision

Making drone data and imagery relevant to growers’ management decisions is essential.

“Sensors create data,” said MicaSense’s Sulik. “What growers need is information. So, what the industry needs is a timely way to reduce the data into actionable information that’s relevant. That’s what needs to be smoothed out. And we are working on that.”

Grignard, of Delair, calls the task a data “bottleneck.”

“The idea of the whole solution is to remove some of the bottleneck with the data at the different steps of the workflow, from acquisition to data processing – that’s not the burden of the crop consultant or the grower.”

One of the analytics tools creates a map for growers to reference.

“We assess the plant health and the plant needs for nutrients and then create a map,” she said. “This map can be valued for prescription, for example, a nitrogen map.” Delair’s DT18Ag also has the capability to count plants or identify gaps in plantings.

But Grignard added that algorithms are not one size-fits-all and results will vary between crops. With strawberry plants, for instance, the plant-counting algorithm works well at early stages, but later the algorithm fails as the plants grow and canopies begin to interlock.

AeroVironment is working on a plant counting algorithm for tree fruit crops, which Dufau said in March was about two to three months away from being available as an add-on to the current system.

Variable rate applicators are another technology developing quickly in precision agriculture. A possible use for drone data, Dufau said, is to make the data transferable from the drone to a variable-rate applicator of fertilizer, pesticides and/or fungicides. Drone data on individual plants joined to a variable-rate applicator that would mean individual plants only get the chemicals they need.

But wherever new technology leads, Dufau said drone-built maps are just going to become more precise in the future.

“You’re going leaf-to-leaf, branch to branch, eventually evaluating plant health out there,” he said. “Those types of precision maps are only going to get better long term. And I see this type of technology just driving some of the areas, especially in specialty crops that haven’t really been implemented.”

– Stephen Kloosterman, VGN Assistant Editor

Top photo: The fixed-wing AeroVironment Quantix features a vertical takeoff and landing feature similar to that of a hover drone.